The continuing pandemic continues to cause disagreement and various reactions. We are becoming a mask vs. maskless society. On Sunday we heard two different pastors pray for unity concerning the virus in their congregations and community. Even many Christians can't agree on government recommendations. Meanwhile Covid rages on.

Recently somebody posted on Facebook a notice that appeared in a newspaper on November 7, 1918. Part of it said "Notice is hereby given that, in order to prevent the spread of Spanish Influenza, all schools, public and private, churches, theatres, moving picture halls, pool rooms and other places of amusement, and lodge meetings, are to be closed until further notice. All public gatherings consisting of ten or more are prohibited." Did folks listen then? I don't know.

Since my grandfather died in this influenza, I have been very interested about it and have been doing some reading. Here are a few of the things I have found.

The 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic, sometimes referred to as the "Spanish flu," killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 people in the United States.. An unusual characteristic of this virus was the high death rate it caused among healthy adults 15 to 34 years of age. The pandemic lowered the average life expectancy in the United States by more than 12 years.

Reported cases of Spanish flu dropped off over the summer of 1918, and there was hope at the beginning of August that the virus had run its course. In retrospect, it was only the calm before the storm. Somewhere in Europe, a mutated strain of the Spanish flu virus had emerged that had the power to kill a perfectly healthy young man or woman within 24 hours of showing the first signs of infection.

Not only was it shocking that healthy young men and women were dying by the millions worldwide, but it was also how they were dying. Struck with blistering fevers, nasal hemorrhaging and pneumonia, the patients would drown in their own fluid-filled lungs.

By December 1918, the deadly second wave of the Spanish flu had finally passed, but the pandemic was far from over. A third wave erupted in Australia in January 1919 and eventually worked its way back to Europe and the United States. Even the U.S. president wasn't spared. In April 1919, shortly after arriving at the World War I peace negotiations in Paris, Woodrow Wilson became seriously ill with influenza-like symptoms. The White House covered up the severity of his condition, claiming Wilson had merely caught a cold from the rainy weather in Paris. Despite nearly derailing the talks, Wilson eventually fully recovered and returned to the U.S that July. I found some interesting comments from folks who lived through those years.

"Nearly every porch, every porch that I'd look at had — would have a casket box a sitting on it. And men a digging graves just as hard as they could and the mines had to shut down. There wasn't a nary a man, there wasn't a — there wasn't a mine a running a lump of coal or running no work. Stayed that away for about six weeks." — Teamus Bartley, coal miner, Kentucky, 1987

"My mother went and shaved the men and laid them out, thinking that they were going to be buried, you know. They wouldn't bury 'em. They had so many died that they keep putting them in garages … garages full of caskets."— Anne Van Dyke, Philadelphia, 1984

"We were the only family saved from the influenza. The rest of the neighbors all were sick. … Directly across the street from us, a boy about 7, 8 years old died and they used to just pick you up and wrap you up in a sheet and put you in a patrol wagon. So the mother and father screaming, 'Let me get a macaroni box … Please, please, let me put him in the macaroni box. Let me put him in the box. Don't take him away like that.' (Pasta used to come in 20-pound boxes.) … 'Please, please, let me put him in the macaroni box. Let me put him in the box. Don't take him away like that.'" Louise Apuchase, Philadelphia, 1987

"That was the roughest time ever. Like I say, people would come up and look in your window and holler and see if you was still alive, is about all. They wouldn't come in." — Glenn Holler, Conover, N.C., 1980

"They were dying — many families losing one or more in their family. It was getting so bad, the deaths, they even, they had to use wagons drawn by two horses to carry people to the grave. I remember seeing them pass the house, seems like to me now it was every day. … At that time, when the phone would ring, when my mother or my father wanted to listen in, and they would turn to us, and they would name the person they just heard had died. It was night and day that you would hear about these people dying. My father never got the flu but he would go to town and buy groceries for the neighbors and take it to the front porch. And we didn't get the flu at all in our family, but it was terrible." — Robert McKinney Martin Jr., 1996

"Another thing about it: people that die, the very stoutest of people. We had a fireman at the place I worked. I used to go out to the boiler room and smoke a cigarette. Me and him were pretty good friends. One day I went out there and they said he was sick. And I went out the next day and they said he was dead. They died just that quick."

It was a sad, sad time. Many lives were changed. Families were devastated. Could that happen again? I fear that it could. It is already happening.

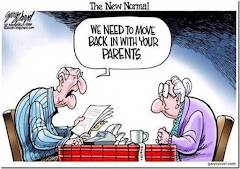

I am concerned that it appears that the American public is not willing to make sacrifices to protect the lives of others. We argue over wearing masks, being separated, staying out of crowds, closing schools, calling off our trips and family gatherings. We want our own way and don't want others to tell us what to do. We try to continue just as though there is no danger.

I doubt that with this new "American Spirit" this country could have survived all these years, especially through attacks from outside foes. It seems like sacrifice is no longer part of our culture. And that is sad!

No comments:

Post a Comment